I bet you remember where you were on the morning of September 11th, 2001 when you heard the news. I’d venture to say that you also remember the city, state, and room that you were standing in. But why is this? Why is it that certain memories are permanently tied to a geographic location?

True, September 11th was a life-altering event, but our brains function similarly with less eventful memories. For instance, maybe it’s a particular bend in a road that triggers a specific conversation, or maybe it’s a song that takes you back to a time and place. Regardless of the trigger, our brains are remarkably good at creating spatial connections. In addition to the conversation, your brain stores related content such as geographic location, time of day, and the individuals present. And when you retrieve this memory, you likely retrieve the geographic information as well.

Does this concept of a spatial storage and retrieval system sound familiar? In the software world we call it a geographic information system (GIS). Using a GIS, we create and store tabular data, along with its spatial component. The strength of this system is that information can be retrieved by either tabular or geographic queries.

At the end of this article you’ll find a link to a Python notebook that explores what the brain’s cognitive mapping system might look like if it were a Geographic Information System.

Much like a GIS, our brains are spatial. As early as 18 months we begin developing cognitive mapping skills to organize the world around us1. These so-called brain maps not only help us navigate our homes and neighborhoods, but they also play an important role in how we organize, store, and retrieve memories.

The remainder of this article will explore some of the science behind our internal mapping, navigation, and memory system.

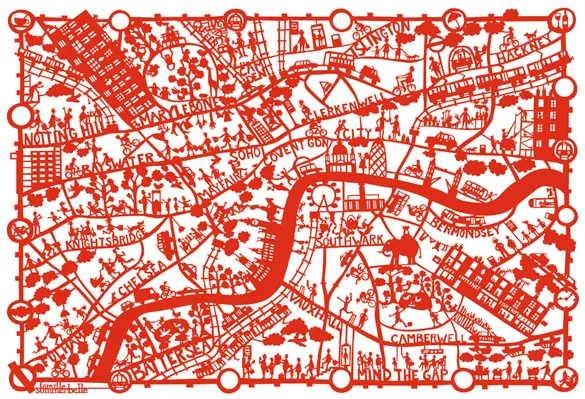

Place Experiences (London Map from “Map of the World: The World According to Illustrators and Storytellers” 2013)

Mapping and Navigation in the Animal World

It turns out that humans are not the only creatures on the planet that are spatially aware. Internal mapping and navigation is widely seen throughout the animal world. Instinctually, it’s linked to foraging and habitat. This can be seen in birds and mammals when they cache food and dig it up later. Their brains are memorizing locations2. Homing pigeons are a good example of using internal navigation; they can return home after being transported hundreds of miles away. Arctic tern travel even greater distances. Using geolocators, a group of researchers found that these birds migrate a total of 43,000 miles as they travel from the North Pole to the South and back again3.

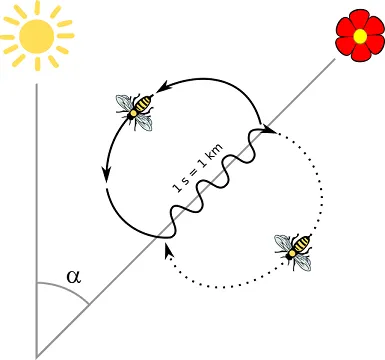

Bees take this a step further and communicate their spatial knowledge with others in their hive. Apart from humans, they are thought to be the only creatures known to do this4. Using the position of the sun as a datum, they share distance and direction to nearby food sources with other bees5. The Smithsonian has captured this remarkable behavior, which is known as the waggle dance, in this YouTube clip, opens in a new tab.

The Waggle Dance (Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.5)

The “Where” in Spatial Awareness

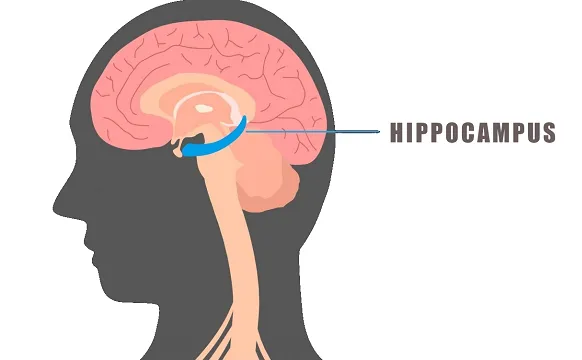

Research shows that in humans, spatial awareness is linked to a specific region buried deep in the brain called the hippocampus (figure 3). Scientists now know that this seahorse-shaped region of the brain (derived from the Greek words hippos, meaning “horse,” and kampos, meaning “sea monster”) functions as both a map and a memory system. The hippocampus is crucial to many parts of life. It allows us to orient ourselves in space and it gives us a sense of direction. You can think of the hippocampus as the brain’s spatial memory system.

The Brain’s Hippocampus (Fillit 2017)

Episodic Memories

In humans, the hippocampus performs an additional function by looking at experience, time, and place. This unique combination allows us to have what are called episodic memories. These are the memories that are linked to a particular place and time - such as where you were when you heard the news about September 11th. The hippocampus is responsible for retrieving these events from the past. It is thought that this capability advanced in humans during the hunter-gathering days as an extension to the spatial functions found in other animals6.

Memory Storage and Patient HM

Much of what we know about the hippocampus and its role in memories can be attributed to a man with no memory at all. As a young boy, Henry Molaison (commonly known as Patient HM) was hit by a car while riding his bike and suffered a brain injury. Soon after that, he began to experience severe epileptic seizures. In 1953, at the age of 27, he decided to undergo experimental brain surgery and have his hippocampus removed. His seizures immediately disappeared, but so did his recent memories.

With Patient HM, it became clear that the hippocampus plays a vital role in memory and storage of memories. It was determined that incoming experiences sit in the hippocampus for a period of time as they are being evaluated for storage. If the experience is strong enough or if we think about the event from time to time, the hippocampus moves this memory to the cortex for long-term storage. The hippocampus coordinates this recording and storing of memories.

This explains why Patient HM could not create new memories. Additionally, because the hippocampus also plays a role in memory retrieval, he was not able to get access to the long-term memories that were stored in the cortex prior to the surgery. His brain could process immediate, sensory experiences but it had no mechanism to store them7.

In addition to a spatial memory system, the brain also contains a remarkable onboard navigation system. A study looking at London cab drivers took a closer look at this.

Internal Navigation and London Cab Drivers

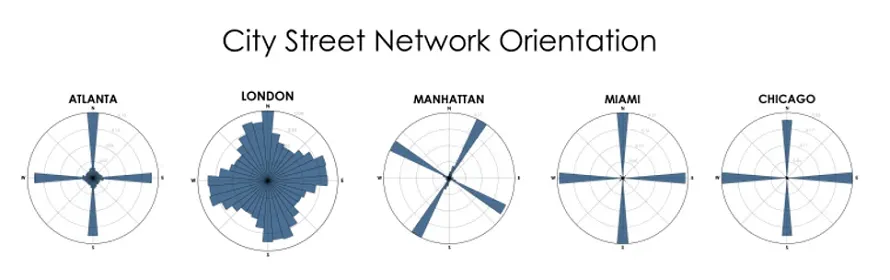

Known as “The Knowledge”, opens in a new tab, all licensed cab drivers in London are required to memorize the city’s 25,000-plus streets as well as thousands of locations and landmarks. The goal is to instantaneously calculate the quickest route between two locations. This requirement might seem excessive in an age when handheld routing devices are in just about everyone’s pocket. But, London’s street network is notorious for being one of the most difficult to navigate. The city’s lack of grid-like layout can be a chore for the uninformed driver8.

The Complexity of Street Networks (Jacobs 2018, opens in a new tab)

So when Neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire set out to study the human brain’s internal navigation, there was no better place than an aspiring London cabbie9.

Because of their navigating abilities, she wondered if these cab drivers have a larger-than-average hippocampus. She got the idea after learning that the hippocampus is larger in animals (including the western scrub jays and squirrels) that stash their food and memorize the location to dig up later.

Maguire’s study observed the drivers for four years as they prepared for the “The Knowledge” exam. Throughout this time, she and her colleagues took snapshots of their brain structure using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans. The results showed a sizable increase in the hippocampus in the drivers that passed the exam. Yet, in the control group, as well as in the candidates that failed the exam, there was no marked increase.

London’s Iconic Black Cabs Financial Times, opens in a new tab

![]()

Additional brain navigation studies were conducted using a highly accurate and interactive virtual reality (VR) simulation of London’s central city as both cab drivers and non-cab drivers navigated the landscape using the Sony Playstation video game, The Gateway (Woollett et al 2009). The game’s streets network was created using map data from the British Ordnance Survey and also simulated entities such as traffic signals, traffic, and pedestrians. Functional MRI (fMRI) scans taken while they navigated around VR London showed that brain activity in the hippocampus was active in both the licensed cab drivers and the non-cab drivers.

The London cab driver studies have shown that the hippocampus plays a vital role in spatial navigation. While creating these mental brain maps, it is thought that the hippocampus grows new neurons and that these neurons further make connections with one another. Researchers think that these findings could have important implications for people with brain damage for diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s10.

Alzheimer’s and the Hippocampus

We know that the hippocampus is important for spatial thinking, navigation, and memory creation - and we’ve seen with Patient HM what happens when it’s completely removed. But, what do we know about the hippocampus when it’s not functioning properly?

Often, the first signs of Alzheimer’s in an individual is a sense of disorientation and getting lost in familiar environments. Additionally, individuals begin to lose episodic memories11.

We now know that Alzheimer’s disease results in a progressive loss of tissue throughout the brain, particularly in the hippocampus. The most rapid loss of tissue occurs in the hippocampus in the earliest stage of the disease. This progressive shrinking is responsible for the disorientation and loss of memory that is the hallmark symptom of Alzheimer’s12. These early signs are tied to a loss of function in the hippocampus.

Currently, there is no effective treatment for Alzheimer’s, however, there is increasing interest in identifying the disease at its earliest stages. The London cab driver studies showed that the brain has the ability to grow new neurons in the hippocampus and that those neurons make new connections. This might explain why the current thinking with Alzheimer’s is that early detection and intervention may be the most effective way to combat the disease12.

Neuroscientist Véronique Bohbot thinks that intervention, focused on executing the hippocampus might help offset age-related impairments or even neurodegenerative disease. She says, “If we are paying attention to our environment, we are stimulating our hippocampus, and a bigger hippocampus seems to be protective against Alzheimer’s disease”.

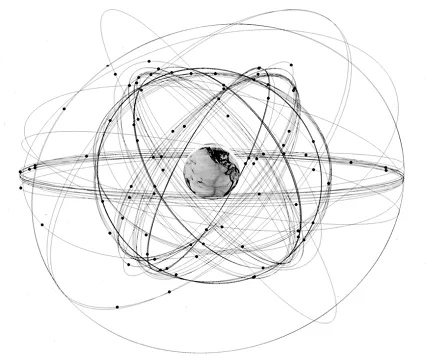

The Effects of GNSS/GPS on the Brain

Again, looking back to the London cab driver findings, the studies show strong activity in the hippocampus when drivers routed themselves based on memory. It makes you wonder how our increasing reliance on GNSS/GPS and turn-by-turn directions affect the overall hippocampal functions.

GNSS Constellations (Tyler Reid, Research Gate, opens in a new tab)

A recent opinion piece in the Washington Post titled, “Ditch the GPS. It’s ruining your brain.”, opens in a new tab sparked some debate on this topic. In this piece, science writer M.R. O’Connor cautions that extensive use of GPS navigation affects our perception and judgment. He continues to say that this dependency disconnects us from our surrounding environment as we follow routes that we don’t remember.

A 2017 article in the journal Nature compared the activity in the hippocampus between a group who navigated with GPS and a group who navigated without it. The study found that there was more activity in the hippocampus in the group who navigated without GPS13.

But, neuroscientist Kate Jeffery, thinks it’s unlikely that extensive use of GPS will result in hippocampal atrophy. She points out that the hippocampus is still pretty busy as people today spend a lot more time now navigating online maps and virtual environments14.

While the verdict is still out on the long term effects of GPS-based navigation, there is plenty of evidence that suggests traditional way-finding is good for our brains. Bohbot said, “When we get lost, it activates the hippocampus, it gets us completely out of the habit mode. Getting lost is good!”.

The brain connections that we make when we explore and navigate our environment help us better connect to the world around while nourishing what is called topophilia - “a strong sense of place, which often becomes mixed with the sense of cultural identity among certain people and a love of certain aspects of such a place”15.

Organizing Life’s Experiences

We now know that our brain is a spatial organ. The hippocampus, in particular, is responsible for mapping, navigation, and memory storage. These functions are linked to additional mechanisms such as episodic and long term memories. Research has shown that when we exercise these functions we see an increase in brain activity. These active neurons not only create new connections but preserve and organize existing ones13.

At the core of these functions is a system that stores and retrieves spatial information. In this context, it’s easy to make a comparison between the brain and GIS. The hippocampus acts much like a file indexing system working with other parts of the brain, that function as a database, making transactions. When we add the episodic memory aspect, it’s similar to enabling the spatial component on the database: memories now contain a geographic location. This explains why places, —such as a bend in the road— or an event —such as September 11th— can trigger the retrieval of certain memories. When we think of September 11th, 2001, we not only remember the event but also the where-we-were.

Neuroscientist Kate Jeffery, who studies cognitive maps, put it well when she said, “A map is a handy way to organize life’s experiences. This makes a lot of sense, since knowing where things happened is a critical part of knowing how to act in the world. The quest now is to understand how memories get attached to this map”16.

Explore Cognitive Mapping in a GIS

Check out this Colab Python notebook, opens in a new tab to explore what the human brain’s cognitive mapping system might look like in a software-based Geographic Information System.

Sources

Footnotes

-

Baby Sparks. “What is Spatial Awareness & How Does it Develop?”. 2019. https://babysparks.com/2019/02/20/what-is-spatial-awareness-how-does-it-develop/, opens in a new tab (accessed December 15, 2019). ↩

-

Jabr, Ferris. Scientific American. “Cache Cab: Taxi Drivers’ Brains Grow to Navigate London’s Streets: Memorizing 25,000 City ↩

-

Amos, Jonathan. “Arctic Tern’s Epic Journey Mapped”. Jan 11, 2010. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/sci/tech/8451908.stm, opens in a new tab (accessed December 13, 2019). ↩

-

Hoxeng, John. American Surveyor. “A Zoological Datum: How Honey Bees Use Datums for Mapping and Navigation”. October 5, 2019. ↩

-

Frisch, Karl von. “The Dance Language and Orientation of Bees”. Harvard University Press. 1993. ↩

-

Garfield, Simon. On the Map: A Mind-Expanding Exploration of the Way the World Looks, 192, 194. New York: Gotham Books, 2013. ↩

-

Kean, Sam. “What Happens When a Neurosurgeon Removes Your Hippocampus”. Wired. May 8, 2014. ↩

-

Jacobs, Frank. “Street grids matter more to your commute than you might think”. Big Think. July 23, 2018. https://bigthink.com/strange-maps/charlotte-nc-has-americas-messiest-street-grid, opens in a new tab (accessed December 22, 2019) ↩

-

Maguire, E., Gadian, D., Johnsrude, I., Good, C., Ashburner, J., Frackowiak, R., & Frith, C. D. (2000). “Navigational Structural Change in the Hippocampi of Taxi Drivers”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 97 (8) 4398-4403. ↩

-

BBC. “Taxi Drivers’ Brains Grow on the Job”. March 14, 2000. https://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/677048.stm, opens in a new tab (accessed Dec 28, 2019) ↩

-

Setti, Sharay E et al. “Alterations in Hippocampal Activity and Alzheimer’s Disease.” Translational issues in psychological science vol. 3,4 (2017): 348-356. ↩

-

Bonner-Jackson, Aaron. “Alzheimer’s and a Shrinking Hippocampus”. BioMed Central. October 15, 2015. https://blogs.biomedcentral.com/on-medicine/2015/10/15/alzheimers-shrinking-hippocampus/, opens in a new tab (accessed Jan 2, 2020) ↩ ↩2

-

Javadi, A., Emo, B., Howard, L. et al. “Hippocampal and Prefrontal Processing of Network Topology to Simulate the Future”. Nat Commun 8, 14652 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14652, opens in a new tab ↩ ↩2

-

Advisory Board. “Can GPS Navigation Really ‘Ruin Your Brain’?”. Aug 5, 2019. https://www.advisory.com/daily-briefing/2019/08/05/gps, opens in a new tab (accessed Jan 2, 2020) ↩

-

Tuan, Yi-fu. “Topophilia: a Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values”. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1974. ↩

-

Jeffrey, Kate. “Maps in the Head: How animals navigate their way around provides clues to how the brain forms, stores and retrieves memories”. Aeon. Jan 25, 2017. https://aeon.co/essays/how-cognitive-maps-help-animals-navigate-the-world, opens in a new tab (accessed on November 24, 2019) ↩